INTERVIEW 009 #rails

Running a Website Monitoring Service with a Boring Technology

with Jamhur Mustafayev

INTERVIEW 008 #static-site

Learn How to Excel at Engineering Management with Developer to Manager

with Siddhant Goel

INTERVIEW 007 #dotnet-core

A Site Where New Quidditch Referees Can Take a Test to Officiate Games

with Marian Dziubiak

INTERVIEW 006 #angularjs

Altair Is a Feature-Rich GraphQL Client IDE for All Platforms

with Samuel Imolorhe

INTERVIEW 005 #nuxt

Postwoman Is a Free, Fast and Beautiful Alternative to Postman

with Liyas Thomas

INTERVIEW 004 #koa

Daily Is a Browser Extension That Replaces Your New Tab with Dev News

with Ido Shamun

INTERVIEW 003 #flask

A Recipe Search Engine and Aggregator Called Recipe Finder

with Bruno Oliveira

INTERVIEW 002 #phoenix

Track How Much Code You Write & What Languages You Use with CodeStats

with Mikko "Nicd" Ahlroth

INTERVIEW 001 #static-site

100k+ Page Views a Month for $5 with a Self Hosted Static Site

with Nick Janetakis

Are you running a site in production? I'd love to hear your story, get interviewed.

Learn How to Excel at Engineering Management with Developer to Manager

What’s your background and what site are you running in production?

My name is Siddhant, and I’m a software developer located in Munich, Germany.

I focus mainly on back-end and infrastructure work, and my programming language of choice is Python. I’ve worked with the language for slightly more than a decade now and also maintain a few open-source modules available on PyPI, so I consider myself fairly useful with the language.

Developer to Manager is a website I launched around October 2018.

It’s a platform to help software developers who are considering a career in engineering management. We interview tech leaders at different stages of their careers, and try to get a sense of what it’s like to be in their shoes.

The motivation is to have an open / free set of resources for developers who are either considering switching to management, or who are new to the job and could use some advice.

At the moment, the site is mostly a solo project. I’m responsible for software development and infrastructure (which I’ll get into later), online marketing, curating content, social media, and basically everything else.

The one thing I decided to outsource quite early on is design. My wife did all the design work, and every now and then I bounce design / product questions off of her. I can’t overstate enough how useful it is to have someone in-house with an eye for product!

A nice side-effect of this manpower restriction is that I try to simplify things as much as I can. As developers, we often have the tendency to use technologies just because they are fun.

Having been through the experience now of getting a product off the ground from scratch, I’ve realized first hand how important non-programming activities are. Because of this, I’ve simplified the software / infrastructure side of things as much as possible. But more on that later!

In terms of traffic, the site is fairly new and as of November 2019, we’re serving a few tens of thousands of requests per month. But due to how the site is built and deployed, we’ve also survived a Hacker News front page event where we received slightly more than 50k requests in a single day.

The site is built using Python / Flask, and compiled to a set of static files using Frozen-Flask which is then deployed to Netlify. We’re currently on Python 3.7.3 and Flask 1.1.1.

What motivated you to use Flask / Python?

Right from the beginning, I was fairly certain that I wanted Developer to Manager to be a static site. Just this one decision eliminated so much infrastructure work that it felt like a good trade-off. Additionally, I wanted the static site generator to be written in Python, so that in case I run into any issues or I want to extend something, I can make the changes myself instead of waiting for someone else.

There are a few really good static site generators (SSGs) in the Python world, the most popular of them being Pelican. What I found though, was that most of them were tailored around the use case of generating “blogs” instead of “sites”. The data models were restricted to the concept of “posts” and “pages”, which is a fairly tight box to break out of.

Luckily, I found Statik which is another SSG written in Python that lets you define custom data models (not just posts and pages) which makes it super useful for generating proper sites.

This set up worked well for a few months, until I started running into its limits. For example, one issue I faced was that I couldn’t generate a sitemap.xml file, because the output format was (and still seems to be) restricted to .html.

At this point, I ran into Frozen-Flask, which is a Flask extension that takes a Flask app and compiles it into a set of static HTML files. I had no prior background with Flask, but all web frameworks tend to support (more or less) the same set of concepts, so getting used to Flask wasn’t too much of an issue.

The only issue I faced was data storage. Flask apps usually store data in a database like PostgreSQL or SQLite, but this didn’t suit my use case that well because all our site data lives in plain-text files (the interviews we conduct are all formatted in Markdown).

I knew that Frozen-Flask would give me basically unlimited flexibility since there’s no abstraction layer there. So I spent a weekend writing a simple Flask extension that enables loading data from YAML-formatted plain-text files into in-memory database tables constructed on the fly.

This allows humans to write data in Markdown and the Flask app to query that data using a SQL interface (Flask-SQLAlchemy, to be more precise).

The above works extremely well in practice. I’ve open-sourced the module under the name Flask-FileAlchemy, and it’s also available on PyPI.

If I had to rewrite the app today from scratch, I would most probably still go for this exact same set up. I like having the comfort of dynamic sites without compromising on the simplicity of static sites. Python is an amazing language to get such tasks done, and it’s improving day by day.

There’s certainly times when I wish for a “normal” dynamic site which would allow me to implement features like user accounts or the ability to automate certain sections on the site. But given the fact that the site is a solo project, this trade-off feels worth it (for now at least).

Is your site a monolith or broken up into microservices?

It’s a monolith. For a repository and application of this scale, microservices would be completely overkill, so I’m very happy for things to be this way.

I sometimes hesitate calling the site “just a static site”, because while it is a static site in production, it’s quite dynamic in development. But it’s a monolith either way.

Currently we only have one git repository where the source code and the data coexist. Since the data is all plain-text Markdown, it’s all version controlled along side the source code.

Flask-FileAlchemy (the data storage layer) expects data for every database table to be in a separate folder. This means that all the site data is very well organized and I know exactly where everything belongs.

In terms of source code, sloccount currently reports about 2,500 lines of Python + Jinja / HTML code (not counting comments). The site is fairly simple and I feel this is also reflected in the size of the source code.

Are you using server rendered templates with sprinkles of JavaScript or is there an API based back-end with a JavaScript heavy front-end?

The primary focus of the site is to display information that is mostly static and mostly text based.

A bunch of HTML / CSS files being served directly by nginx serves that purpose really well. There are no API endpoints or back-ends to worry about, so I don’t have to muck around with JavaScript heavy front-ends hooked up to JSON APIs. While these architectures exist for a reason, using them to display text / static information feels like overkill.

The front-end uses Bootstrap. The only JavaScript on the site is the one shipped with the framework. Similarly, in terms of CSS, I try to stick to the helper classes that Bootstrap provides, so I don’t have to write any extra CSS. My aim for the site design is that it should be minimal but functional. This reduces the front-end work even further.

The only CSS / JS modification on top of Bootstrap is the font-family definition. Everything else is basically “factory settings”.

So far, I’m happy with this decision. It keeps things rather simple and minimal, and the amount of software engineering I have to invest stays small. Like I mentioned before, there are drawbacks of this approach but the trade-offs so far seem to have been worth it.

What does the rest of your tech stack look like?

Apart from Flask, I use Brunch to concatenate and minimize all the front-end assets (which is basically just the bootstrap .css + .js files and dependencies). I chose Brunch because the configuration is simple and so far it has “just worked”.

Because the site is static, things like databases, Docker, queue back-ends, etc. aren’t there in the stack. This might change in the future in case the site moves to a more dynamic nature, but at the moment that’s not the case.

The domain was originally registered on Gandi. I’ve used them for almost all the domains I’ve registered in the past and so far it seems like they deliver quite well on their “no BS since 1999” stance. Although, the DNS configuration is all in Netlify.

Which external SAAS tools does your site depend on?

Apart from Netlify that I already talked about, not that many.

For analytics we use Fathom. It’s a privacy respecting analytics service, so apart from not tracking / storing any personal user information, it also helps with the strict data privacy laws in Germany where I’m currently based.

EmailOctopus is used for sending out email newsletters. We were using Mailchimp earlier, but their pricing does not seem to be aimed at smaller businesses. EmailOctopus is much cheaper, and seems to have a much smaller (and more thought-out) set of features which makes it quite easy to use.

Which cloud hosting provider or platform are you using to host everything?

The site is deployed on Netlify, which is a SaaS platform that lets you host static sites (among other things).

While they offer an entire suite of products built around the static site eco-system (including things like user management, forms, lambda functions, etc.) we’re using only the “hosting” bit.

The idea is that you upload a bunch of HTML files to Netlify (or connect a Git repository if you want continuous delivery), and then they handle the rest (stuff like nginx, load balancing, caching, SSL certificates, etc.). This lets me focus on the product and not worry about managing and configuring the underlying servers and the software installed on them.

Their free offering is very generous, so hosting the site doesn’t cost me anything right now. I have no idea what hardware my site ends up on or what operating system it’s using (and to be honest, I’m not sure if I’m interested in knowing either), but it’s definitely good enough to have survived a Hacker News spike.

What does your deployment process look like?

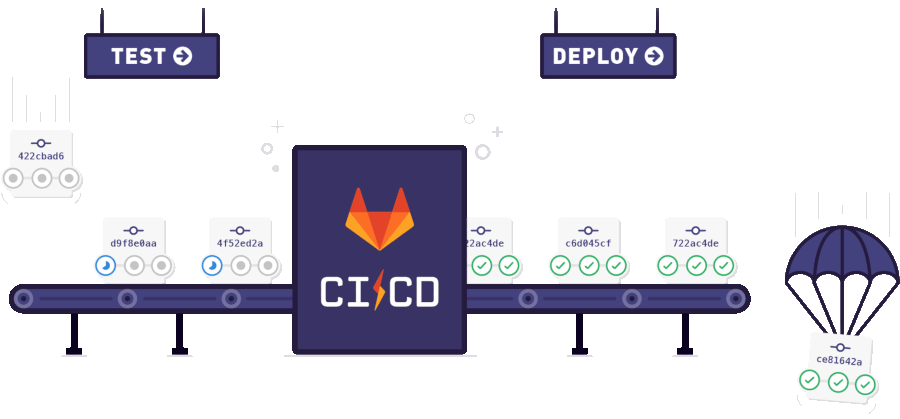

Before deciding whether or not to deploy, I first check that the CI status is green. We’re using Gitlab for source code hosting and the in-built Gitlab CI for testing.

At the moment, the CI checks for linting issues in the Python codebase (using black and flake8) and runs a couple of simple tests to make sure that all the pages on the site can be rendered without any errors and contain what they’re supposed to contain.

The deployment is split into two stages. It starts with generating the site’s content and then uploads it to Netlify.

To generate the site, we first use brunch to compile and minimize the front-end assets. Then Frozen-Flask “freezes” the Flask application into a set of HTML files. All the resulting files are written into a build/ folder on disk.

Once this folder is ready, we use the netlify-cli tool to upload the contents of this build/ folder to Netlify. That’s basically it.

Once netlify-cli has done its job, the site is live. I’ve put these two steps into a Makefile so I don’t have to keep them in mind all the time. So far, I’m happy with how well this process has worked and how simple it is in practice.

How have you planned for disasters, unexpected events or malicious users?

One of the advantages of running a static site is that there are not too many moving parts, so there’s not that much to plan on this front. Besides, Netlify provides the option of rolling back to a previous build anytime so that kind of serves as a “database backup”.

In terms of monitors / alarms, there’s one monitor set on Uptime Robot that checks the main page every 5 minutes and will send me an email if something is down, but that’s pretty much it.

What’s your advice for others who are running similar stacks in production?

Keep things simple. Pick the simplest tech stack possible that contains the least number of moving parts. More often than not, this is also going to be the best way for your product to run in production. Overcomplicating things is just going to come back at some point and bite you.

Keep things boring. The web dev ecosystem is changing constantly, with new frameworks coming up almost every single week. This is great if you want to experiment or keep up with trends but when you’re putting a product in production, picking a boring stack is a very good strategy.

Basically, use things that have been proven to work well and you’ll almost never go wrong.

The one resource on this that I highly recommend going through is an article called Mental Models I Find Repeatedly Useful, written by the founder of DuckDuckGo. I feel that a lot of these models can be applied to the problem of selecting a tech stack in production with good results.

Where can we go to learn more?

You can find my personal website at https://sgoel.dev, and my Github at https://github.com/siddhantgoel.

My contact information is on my website. If you have any questions or comments about this interview, Developer to Manager or anything else really then feel free to reach out!

– Siddhant Goel, Software Developer

Dec 11, 2019

✏️ Edit on GitHub